Table of Contents

Revival of Millets: A Growing Trend in our Food Systems

Millets have long been a staple in the diets of indigenous communities in Odisha, providing a source of food security for small and marginal farmers residing in fragile agro-ecological regions. These crops are climate-resilient, able to thrive in rainfed or dryland conditions with minimal water requirements. Additionally, they are highly nutritious. The indigenous communities have traditionally practiced mixed farming and crop rotation, which are well-suited to the local agroecology, and have weathered extreme climate variabilities over time. The preservation of these agricultural systems is crucial to address climate change issues, both locally and globally.

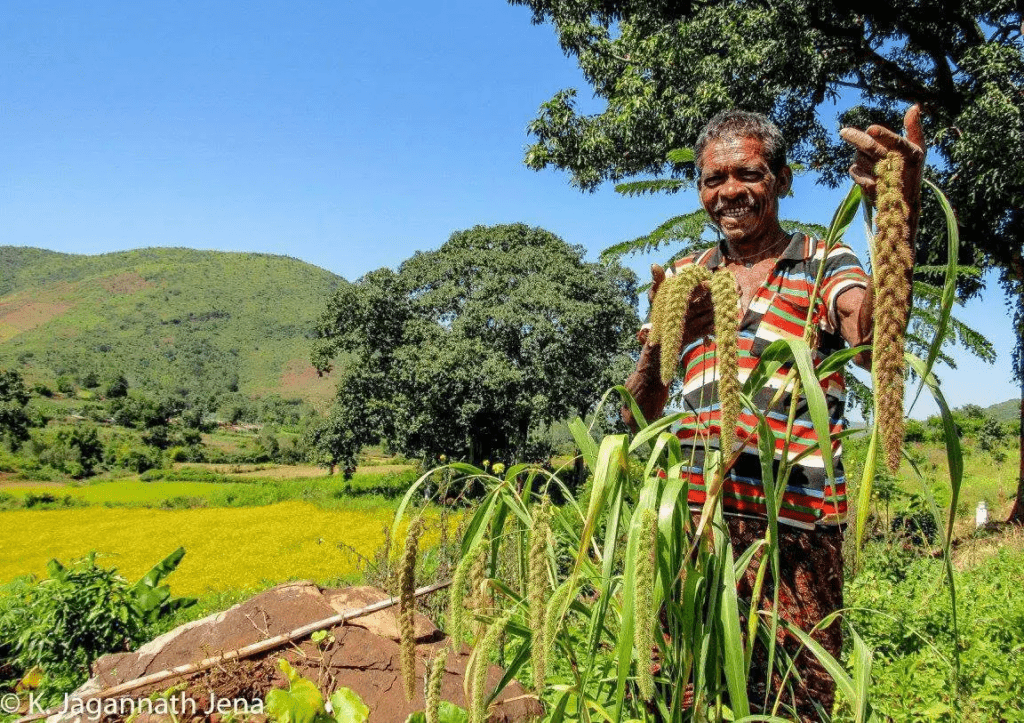

In the past, farmers in India used to cultivate a variety of millets such as ragi, kodo, suan, kosala, kangu, gurji, etc. using organic farming methods. Millets were once widely cultivated in different regions, including the eastern ghats, until about 20-25 years ago. The list of millets includes Jowar (Sorghum vulgare), Pearl millet (Pennisetum typhoides), Little millet (Panicum sumatrense), Proso millet (Panicum miliare), Barnyard millet (Eichinochloa sp.), Foxtail millet (Setaria italica), Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum), and Ragi (Eluesine coracana). Among these, ragi is more popular in terms of acreage. Millets are well-suited for cultivation in poor soils with low water-holding capacity and are dependent on monsoons for their growth.

Tribal communities have been practicing shifting cultivation on medium and uplands along the hill slopes, cultivating millets during June to September, which have been the primary source of food and nutrition for them. However, changes in dietary patterns have been observed in the last two decades, with more rural households preferring rice due to its availability under the Public Distribution System (PDS). A report by the National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, reveals that compared to rice, millets have higher nutritional value, including better mineral, protein, fat, and iron content. The iron content in millets is particularly crucial for fighting malnutrition and anemia, which are widespread in the region.

In recent times, Ragi is gaining popularity in urban areas as a health-promoting food, and is gradually becoming a staple food in society. However, there is a risk of turning millet cultivation into a monoculture of only a few varieties if a commercial approach is taken. This would lead to a loss of crop diversity and hinder in situ evolution with climate change. It also puts the crop at risk of being destroyed by natural calamities, disease, or pest outbreaks. Therefore, it is necessary to develop strategies to maintain land races alongside commercial cultivation.

Sustainable Practices for Agriculture, Animal Husbandry and Forestry

Local indigenous communities have been affected by extreme weather variations and climate change, leading to changes in crop planning, land-use patterns, crop production, yields, and emergence of pests and diseases such as Giant African Snails, stem borer, bacterial, and fungal diseases like Blight and Wilting disease. As a result, there have been changes in cropping patterns, distress migration, and impacts on the livelihoods of local Kondh communities. Over the last two decades, these communities have become increasingly aware of changes in weather and climate.

The past decade has seen a significant rise in temperatures, with an increase of over 1.4 degrees Celsius. These changes, along with alterations in soil conditions, have caused a shift in local farming practices and land-use patterns, as well as in traditional agriculture systems. Furthermore, extreme weather variations, such as the delay in the onset of the South-west monsoons, high-intensity short-duration rainfall, erratic rainfall, prolonged dry spells, and high variability in diurnal temperatures, have led to outbreaks of epidemics among cattle and livestock. These factors have had an adverse effect on food production and productivity, reduced milk production and yields, affected water systems and local biodiversity, and more.

Over the last two decades, Kandhamal has witnessed a rise in the frequency and recurrence of natural disasters such as droughts, flash floods, and cyclones, which have significantly impacted people’s livelihoods and the agriculture sector. The warmer weather has also extended to the winter months, further exacerbating the situation. Unfortunately, there is a lack of disaster preparedness among the reference communities in Daspalla and Tumudibandha Blocks with regard to natural disasters and climate change.

A majority of the farmers in the area practice subsistence farming, with only a small percentage of their produce (10-20%) being sold in local markets. Shifting cultivation, also known as slash-and-burn agriculture, is the primary means of food production for the local tribal communities, known as the Kondhs, who refer to it as “dongar chas” or “podu chas”. However, the practice has seen a reduction in rotational cycles from 3-5 years to every alternate year, leading to concerns over forest fires. Although such fires are not common, they have been reported in the area.

The primary crops grown under the shifting cultivation system practiced by Kondh farmers are minor millets such as finger millet (ragi), little millet (kosala), and kangu, along with intercropped arhar. These crops are typically cultivated during the Kharif season, which runs from June to September. The podu landholdings on hill slopes tend to average between 0.5-3 acres in size. Notably, Kondh farmers do not use manure or chemical fertilizers in their shifting cultivation practices.

Engagement of Local Community

The local communities in Nayagarh and Kandhamal districts cultivate a variety of minor millets like Ragi – Muskul, Sika, Bodo Mandia, Taya, Sano Mandia, Kontamita, Dussera, Muskul, Sika, Kongora, KMR 204, among others, using seeds of local varieties. In addition, other minor millets such as Suan, Kangu, Kerwa, Kodo, Kosala, etc. are also grown. These millets are consumed in their daily diets along with rice, greens, chillies, and salt, forming an important part of the local community’s diet.

Local communities have reported a decrease in crop diversity, food crop production, and productivity, as well as a reduction in the production of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) and horticultural crops, particularly over the past two decades.

The local communities in the region depend on multiple sources of income, including agriculture, casual labor, and the collection and sale of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs). Livestock rearing is also a significant source of income, but distress sales of livestock are common. The average household income in the region ranges from INR 5,500 to INR 30,000. During the COVID-19 pandemic, over 80% of rural households in the region have had to take loans or mortgage their valuables to cope with the crisis. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme provides a major source of income for many households, while poor households belonging to elderly people, widows, and persons with disabilities receive monthly pensions.

The rural households in Kandhamal district rely heavily on the subsidized Rice provided by the State Government, which costs Re.1. More than 80% of these households experience food insecurity for a period of 3 to 5 months each year, with August, September, and October being the most affected months. Child malnourishment is high, with over 23% of children being affected, and more than 50% of women and children suffering from anaemia. Most tribal households have poor dietary diversity, with “Mandia Pej” (Ragi gruel), rice, Saag (green leafy vegetables), salt, and green chillies forming their staple breakfast, lunch, and dinner. People primarily consume carbohydrates, with a limited intake of lentils, milk, and meat.

The primary sources of income for local communities include agricultural labor, the sale of Siali (Bauhinia vahli) and Sal leaf (Shorea robusta) plates, small-scale poultry and goat farming, and remittances from migrant workers. However, a sudden glut of agricultural produce and non-timber forest products (NTFPs) has led to distress sales of these commodities. Furthermore, the region lacks adequate cold storage facilities at the block and district levels.

The local communities rely on the forest for their livelihoods for more than half of the year, as they gather food, fodder, building materials, medicines, and fuel wood. However, they are hesitant to collect many non-timber forest products (NTFPs) due to their fear of forest department authorities. The involvement of intermediaries in the collection, processing, and sale of major agricultural produce and NTFPs results in minimal profits for farmers and primary collectors. Leaf cups and plates made out of Siali and Sal leaves are common products produced by most rural households.

Distress migration is a harsh reality for many impoverished households in Kandhamal, with approximately one in three households affected. The migration is predominantly seasonal, with adult members seeking employment opportunities both inside and outside of the state. Generally, male members migrate during the months of August/September and return in February before the main cultivation season (Kharif). The majority of migration takes place between July-August and November-December when the community awaits harvest. These months coincide with periods of food scarcity. Most of the migrants move to Andhra Pradesh and Telangana for work in brick kilns and to Kerala to work in stone-crushing units, rubber and tea plantations. Remittances from migrant family members range between INR 3,000 and INR 12,000, which are used to purchase basic necessities by the family members who remain behind. However, last year’s lockdown imposed to control the COVID-19 pandemic prevented many migrant workers from returning to their villages, depriving their families of even this modest income.

Pic – Daspalla Seed festival, Nayagarh

The awareness and promotion of millets are increasing rapidly, with events being organized in various locations and the significance of millets being emphasized. In order to conserve these valuable resources, the government, private sector, and civil society have come forward to support millet cultivation by providing necessary inputs such as irrigation facilities, seed supply, and incentives for cultivation.

Millets are generally less reliant on chemical inputs and are resistant to pests and diseases. As a result, it would be wise to avoid or minimize the use of pesticides rather than treating millets as a fully commercial product, which would make their cultivation expensive with high external inputs. Nevertheless, the low input requirements for millets mean that companies traditionally associated with selling agricultural inputs like fertilizers and pesticides show little interest in millet cultivation and may even discourage farmers from taking up these crops. This lack of commercial involvement has also weakened advocacy for millet cultivation in public forums. However, there is growing interest in reviving millet cultivation, driven by the Millets Mission, local NGOs, and farmer organizations in Odisha. The government has pledged support for millet cultivation by providing irrigation facilities, seed supply, and incentives.

The Government of Odisha, through its Millets Mission and local NGOs, has been making efforts to meet the growing demand for millets among urban consumers. These efforts aim to increase production, improve processing, add value to the products, and enhance packaging and branding. As a result of these efforts, cuisines made from millets have become increasingly popular in urban areas, emerging as a new food trend.

NIRMAN initiated its work with local indigenous communities in 2012 to promote mixed, biodiverse, and sustainable agriculture practices and ecological farming, by reviving indigenous farming practices. As a preliminary step, Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) exercise was conducted in all the villages to gather baseline information on various aspects, such as household income, the status of indigenous agricultural practices followed, and the extent of seed diversity. To encourage the communities to revive their indigenous agricultural practices, a village-level meeting was organized to discuss the issues related to the erosion of the indigenous crop diversity, indigenous agriculture practices, and sustainable agriculture.

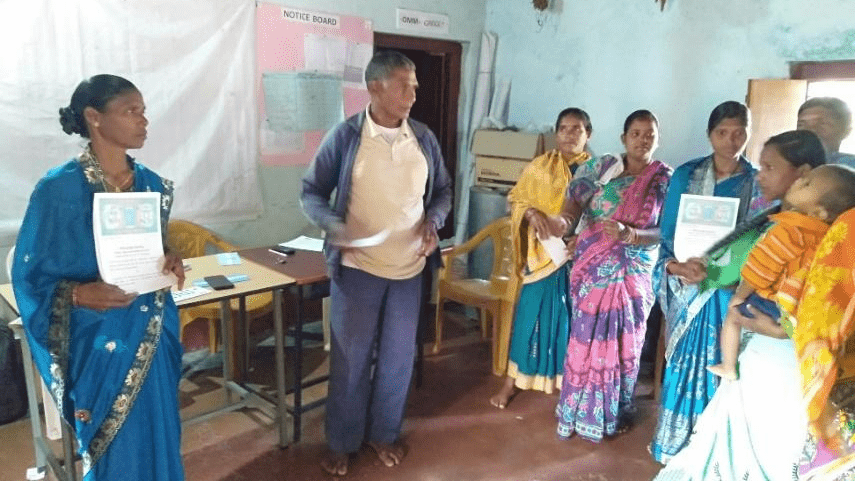

During the first year of the project, trainings were conducted to promote millet-based mixed farming. In the second year, training was focused on sustainable agricultural practices at the village level, with a specific emphasis on restoring seed diversity. To revive the indigenous mixed and biodiverse farming system, women were encouraged to practice mixed farming. Our intervention focused on promoting women-led approaches, empowering them to take control over the food production system, and conserving indigenous agro-biodiversity.

Women-led village meetings were held to establish Village Level Institutions (VLIs) and promote community-based seed banks. In total, 21 VLIs were established and members were trained in the management of millet-based community seed banks. These seed banks were intended to meet the seed requirements of the community, and currently, 27 seed banks have been established, serving around 600 farmers in 27 villages. To conserve indigenous crop diversity, the required heirloom seeds for the community were assessed and provided as one-time seed-capital for conservation. 12 indigenous crop varieties of local preference were supplied to local communities, resulting in the successful revival of these varieties within one cropping season.

At present, the community-based seed banks have expanded to maintain heirloom seeds of 55 indigenous crops, including a variety of millets, maize, pulses, vegetables, and edible tubers. Communities are now cultivating 7 varieties of indigenous paddy, 6 varieties of indigenous maize, and multiple types of millets, including 3 varieties of finger millet, 3 varieties of little millet, 2 varieties of barnyard millet, 2 varieties of pearl millet, and 3 varieties of foxtail millet. In addition, they are growing 2 varieties of sorghum, 4 varieties of pigeon pea, 2 varieties of cow pea, 3 varieties of rice bean, 4 varieties of country bean, 2 varieties of black gram, horse gram, and 17 types of edible tubers, under a millet-based mixed farming system.

Indigenous crops such as castor, mustard, niger, sesame, various vegetables, 17 edible tubers, turmeric, ginger, garlic, chilli peppers, onions, and other locally grown coarse grains and pulses are also cultivated by the communities. Women farmers have been leading the way in the resurgence of indigenous crops, managing community-based seed banks, and conserving indigenous agro-biodiversity.

Indigenous women take charge of storing seeds for the upcoming growing season. The seeds are stored in traditional seed storage structures such as “Dullies,” “Puda,” and earthen pots that are hung over the kitchen. Specific methods of storage are followed within the households, and the seeds are not usually disturbed by moving them from one place to another.

Also read – Regenerative Agriculture In An Era Of Climate Change

Challenges in Millet Promotion

One of the challenging issues faced by forest dwellers is the lack of recognition of their rights over their cultivated land and community resources. Since women play a crucial role in farming, efforts have been made to legally recognize the rights of local communities over their customarily used individual lands, which are also suitable for millet-based farming systems. To achieve this, village-level meetings were organized to educate local communities about the provisions of the Forest Right Act, 2006 (FRA), and the process for filing claims over their lands. The community volunteers provided support for the entire process. As a result, 89 households received individual land rights over their customarily used land, with joint ownership titles provided to women.

The recognition of individual and community land rights has helped strengthen the stake of the Kutia Kondh communities in their forest resources, which are essential for food production and food sovereignty. In the past, women in remote villages held the knowledge of seed conservation and storage, which empowered them both at home and in the community. However, with the increasing use of hybrid seeds by men, much of this valuable knowledge has been lost.

NIRMAN’s approach involves working on both the “demand” and “supply” sides of the food system. On the “demand” side, the organization promotes local varieties of food crops, including minor millets, paddy, pulses, oilseeds, and vegetables, while also encouraging mixed cropping systems and sustainable agriculture practices. On the “supply” side, NIRMAN promotes value chains for both agriculture and non-timber forest products (NTFPs), connecting farmers with markets where private sector actors can play a crucial role in supporting sustainable agriculture. The organization also supports both “on-farm” and “off-farm” livelihoods, and has made investments to support adaptation measures in the areas of agroecology, natural resource management, and human capacity development.

Multi-faceted Benefits of Millet Cultivation for Farmers’ Livelihoods and Well-being

NIRMAN is actively promoting the cultivation of major and minor millets in the region. The Millet Mission project has given a further boost to this initiative. Typically, minor millets are grown for a period of 2-3 months during the Kharif season. However, small and marginal farmers who cultivate highlands usually prefer to grow paddy for food security reasons. To promote crop diversification, partial substitution of paddy with alley cropping (mixed cropping) is being advocated. Various combinations of crops are being popularized under mixed cropping, and steps are being taken to grow early varieties of food crops, including millets, in some of these lands.

In Nayagarh and Kandhamal districts, some women have voiced their concerns about the challenges of cultivating minor millets in the region. Over the last 20 years, there has been a significant decrease in both the area under cultivation and crop yields, with reductions of around 25-30% and almost a third, respectively. This decline is mainly due to factors such as the unavailability of local indigenous seed varieties, restrictions on “Podu chas” cultivation on hill slopes by the forest department, increased human activity, widespread deforestation, and accelerated soil erosion.

NIRMAN has assisted farmers groups by providing processing units for minor millets, including solar-based ones, in remote tribal hinterlands. Women’s groups are involved in the aggregation, processing, packaging, and marketing of millets, thereby earning better income (over double the raw produce).

How Does Shifting to Millet Farming Affect Farmers’ Food Security?

In the KBK (Koraput-Balangir-Kalahandi) districts, most farmers are only able to produce enough food for their families for 3 to 4 months, leaving them food insecure for the rest of the year. Even with the government providing rice at a highly subsidized rate of Re. 1 per kilogram, rural households struggle to meet their food requirements. The situation is worsened by the fact that the area under minor millet cultivation has been steadily decreasing over the past 30 years.

The period from August to October is characterized by food scarcity in the region, leading to a higher incidence of migration among farmers, driven mainly by economic factors. The majority of farmers (90%) save their own seeds for use in the next growing season. However, traditional/desi varieties are only available with a few large farmers in the district. Productivity for most field crops is lower compared to the state and national averages, due in part to limited soil and water conservation/management practices.

Minor millets, vegetables, ginger, and turmeric are among the crops cultivated by smallholder farmers, who constitute over 80% of the farmers in the KBK districts with land holdings less than 2.5 acres. These farmers practice subsistence farming, with most of the food produced being used for household consumption. Only a small portion, typically 10-20%, is sold in local haats/shandies. The cropping pattern has remained largely unchanged for the last thirty years, with a mix of paddy, minor millets, pulses, and vegetables being grown in rotation. Unfortunately, many traditional/desi landraces of minor millets are either no longer cultivated or have become extinct.

COVID Aftermath

Rural households in the study area have high levels of indebtedness, with over 80% of them having taken loans from various sources including family members, relatives, and landlords. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, women have resorted to mortgaging their gold and valuables to sustain their families. This suggests that the rural households are facing financial challenges and may be struggling to make ends meet. The high levels of indebtedness could also indicate limited access to formal financial institutions and lack of adequate credit options for these households.

Most households have faced a shortage of cash that can be easily used to make purchases or pay bills in the past two years. This can be due to various reasons such as a decrease in income, increase in expenses, or economic instability. As a result, households may have had to rely on credit, borrow money, or cut down on their expenses to manage their finances.

Value Addition Initiatives Promoted by Government under the Odisha Millets Mission

Setting up decentralized Processing facilities: Lack of modern processing facilities is recognized as a significant obstacle to the revival of millets. To facilitate easy access to millet grains, the government is promoting the establishment of decentralized processing facilities in each block. The facilities that will be promoted in each block include:

- To facilitate the revival of millets, the establishment of modern processing facilities has been identified as a critical requirement. It is envisioned that promoting such processing facilities will provide farmers with easier access to millet grains. As a result, it has been proposed that each cluster of villages or Gram Panchayats should have at least one processing unit or enterprise, which includes de-huller, de-stoner, pulveriser, and other related equipment.

- The government aims to establish at least one pulverizer in each Gram Panchayat, with a specific focus on Ragi processing.

The successful establishment of such enterprises is expected to encourage household-level consumption and kick-start local enterprises. It is also anticipated that, with increasing production within the block, larger processing facilities will be established by private partners.

Custom Hiring Centres (Appropriate Farm Mechanization): To reduce the drudgery and increase the efficiency of crop management, custom hiring centers for appropriate farm mechanization are being established at clusters of Gram Panchayats. These centers offer a range of useful equipment, such as cycle weeders, sprayers, pump sets, irrigation equipment, threshers, bio manure preparation containers, sieves, and fencing materials. The aim is to provide farmers with access to necessary machinery and tools for post-harvest operations and clean millet harvesting. Based on the needs of the community, the equipment can be hired for suitable crop management.

The role of millets in food distribution systems and their evolving markets, both domestically and internationally

Under the Odisha Millets Mission, the government has started procuring millets, with a Minimum Support Price (MSP) set up for Ragi. However, other types of millets do not have an MSP yet. As a pilot project, millets have been included in the Public Distribution System (PDS) and Mid-Day Meal (MDM) schemes in the state. Additionally, government outlets in various towns and cities also sell millets. Despite this, agriculture produce, including minor millets and Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP), are mainly sold in local shandies or “Haats” in small towns, Gram Panchayat Headquarters, and Block Headquarters. There are only a few government marketing agencies, and ORMAS, TRIFED, and Mission Shakti/OLM are the major ones. However, local communities have limited awareness and knowledge about market information and marketing channels.

The Minimum Support Price (MSP) for most Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFPs) is currently low and has not been revised for over three decades. Additionally, there are still issues with non-procurement of agricultural produce and NTFPs by government agencies.

There is a lack of storage facilities, such as cold storage and godowns, for agriculture produce and NTFPs at the community, Gram Panchayat, Block, and district levels. As a result, farmers are forced to sell their produce at a lower price. Additionally, farmers have limited or no information on market prices, crop loans, and crop insurance. The value addition initiatives, such as sorting, processing, packaging, and branding, are minimal or non-existent, and there is a lack of skill, knowledge, and facilities for this.

Most of the agricultural produce and NTFPs in the state face challenges in marketing, with traders and middlemen procuring them from haats both within and outside the state.

The international marketing of such produce is in its early stages, with only a few civil society actors starting to connect with international consumers through digital marketing channels, particularly in countries like Germany. However, the availability of market actors is limited.

Participation of Women

Pic – Recognition of women farmers

Women’s significant contribution to agriculture is undeniable, as they participate in more than 70% of the activities involved in farming, such as sowing, transplanting, weeding, irrigation, harvesting, cleaning/winnowing, thrashing, seed storage, and primary processing, in addition to their regular household responsibilities. However, due to patriarchal societal norms, women own very little land (less than 12%) and have limited access to property resources. Moreover, the region experiences differential wage practices, with women agricultural workers receiving lower pay than their male counterparts (Men – INR 250; Women – INR 200).

NIRMAN facilitates and encourages young entrepreneurs in the agriculture and allied sectors by connecting them with private companies for procurement and marketing. These opportunities are available in specific agricultural production clusters in Nayagarh and Kandhamal districts, including Siali (Bauhinia vahli) leaves, ginger, turmeric, sal leaves, vegetables, apiculture (honey), small-scale poultry, and goat farming. NIRMAN also collaborates with private sector actors to promote and support ecological farming practices in Odisha, which benefits both the farming communities and private sector companies.

NIRMAN aims to strengthen the existing systems to enhance the efficiency and reach of government development schemes, entitlements, benefits, and services to the local communities. To achieve this, NIRMAN plans to work closely with government authorities and frontline staff at the local, Gram Panchayat, Block, and District levels.

Millet’s data of 2021-22, NIRMAN, Odisha

| Sl No. | Block | No of village covered | No of farmers involved | Total area covered (in Ha.) | Total surplus ragi procured (through TDCC) | Total money received through Procurement (in INR) | Total incentive transferred to the farmers account (INR) |

| 1 | Tumudibandha | 212 | 2255 | 1081.4 | 3850.69 | 12965755.1 | 1659800 |

| 2 | Kotagada | 75 | 1096 | 700.2 | 3762.74 | 4798142.9 | 1602000 |

| 3 | Dasapalla (1st Yr.) | 22 | 496 | 190.95 | 0 | 0 | 1699659 |

| 4 | K.Singhpur | 57 | 1675 | 1075 | 2500 | 8442500 | 1069000 |

| Total | 366 | 5522 | 3047.55 | 10113.43 | 26206398 | 6030459 | |

Research and Policy: Creating an Enabling Environment for the Promotion of Millets

Millets are highly nutritious and well-suited to address hunger and malnutrition. However, some government policies aimed at addressing malnutrition in the region may inadvertently promote monocultures, which can lead to a loss of biodiversity and a different type of malnutrition. Therefore, it is crucial to develop strategies that promote the cultivation of millets using traditional methods that are best suited to the local agroecology while ensuring the preservation of biodiversity.

Odisha’s agriculture policy neglects the promotion of millets despite its potential to reduce maternal and child malnutrition, particularly among the high tribal population. This lack of commitment towards millets contradicts the state’s long-term goal of reducing malnutrition.

NIRMAN emphasizes the importance of people-centered and evidence-based policy and advocacy work. To achieve this goal, it collaborates with other NGOs, state and national-level networks, alliances, and social movements such as the Right to Food and Work campaign. NIRMAN works with both “Rights Holders” and “Duty Bearers”, including the state and national government and marginalized communities and their associations to influence policies. This involves close coordination and lobbying efforts at the local, state, national, and international levels.

NIRMAN strives to empower local communities by providing information and awareness about major government development schemes and flagship programs related to food security and nutrition. These include the Public Distribution System (PDS), Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), Mid Day Meals (MDM), POSHAN 2.0 (National Nutrition Mission), major social security schemes like Old Age Pension (OAP), widow pensions, and special schemes for Persons with Disabilities (PWDs), as well as strengthening the maternal and child sectors and the Mahatma Gandhi National Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). Such efforts are crucial to ensure food and livelihood security for the poorest households and the most vulnerable communities.

Recommendations for Policy Changes to Promote Millets

Policy changes should prioritize infrastructure development in regions where millets are grown. This is crucial for ensuring that cost-effective techniques such as System of Millet Intensification (SMI) and line sowing can be implemented effectively by farmers. Additionally, it is essential to encourage and practice the cultivation of several millet varieties to promote crop diversity.

- The government has included millets in the public distribution system and supplementary nutrition programmes on a pilot basis in Odisha, but there is a need to scale up these initiatives at the State level. To encourage millet farming, farmers should be incentivized and provided with financial support for processing, storage, and marketing. Specific value addition practices such as grading, sorting, cleaning, processing, and packaging should be supported, and millet marketing should be promoted through the State Livelihood Mission and non-profit organizations in rural areas. Groundwater overexploitation for plantation crops needs to be curbed to maximize millet production.

- Mixed cropping, intercropping, and crop rotation models should be promoted, especially in KBK districts, using organic farming techniques. The government should devise policies that consider the health and economic status of the farming community while promoting millets as a health food in areas where land holdings are marginal.

- The State Government has announced the distribution of forest patta on a mission mode by 2024, which opens up opportunities for local forest communities to access and claim Individual Forest Rights (IFR) and Community Forest Rights (CFR) land titles. Owning land will create opportunities for food crop cultivation, including millets, in the State.

- Community-level monitoring of food and nutrition schemes and programs will be crucial for sustainability. It depends on local organizations to build meaningful relationships with government authorities to make the project sustainable.

- Compulsory maintenance of landraces by the government and seed producing companies will help maintain biodiversity and lower the burden on farmers for landrace maintenance.

- Limiting acreage under orchard crops/commercial crops as a percentage of land holding for farmers with larger holdings will promote a healthy balance in the environment, ensure diversity, and nutrition security while helping farmers with more income. Proper management practices and planning need to be undertaken to grow both trees and millet crops, so short term financial gains are not offset by the effects of climate change in the future.

- Involving private sector companies in promoting millets while preserving landraces by the companies can be done. But there is a risk of promoting monoculture. Health supplements can lead to improved health of women/children and ensure millet consumption, which may help to create a better market for millet-based food products.

- Inclusion of millets in the PDS, Mid Day Meal (MDM) scheme, and procuring from local sources and scaling it up at the State level is important. This will maintain local production, provide better nutrition to children, and retain their habit of consuming millets.

- There is a low Minimum Support Price (MSP) for most food crops, including millets and NTFPs in Odisha, which may indirectly promote the decline of millets and lead to a different kind of malnutrition while alleviating hunger in the region.

- Tribal farmers traditionally practice mixed farming and crop rotation, which are best suited to the local agroecology. Such traditional cropping systems need to be supported and promoted for sustainability to address climate change issues locally.

- Women play a significant role in fighting climate change and eradicating chronic hunger and malnutrition. The bond between millets and women in these tribal tracts is indispensable and cannot be broken. The fine line between substituting wealth for health needs to be precisely defined to avoid health-related problems in the region suffering from endemic malnutrition.

To promote the cultivation and propagation of local varieties of millets, it is crucial to develop effective marketing strategies that prioritize their value in comparison to cash crops. While tree crops have helped farmers break free from poverty, it is important to educate them on the significance of continuing to cultivate minor millets in light of climate change. Tribal farmers have a history of practicing mixed farming and crop rotation, which align well with the local agroecology and have proven successful in the face of climate variability. To address climate change locally, it is imperative to support and promote these traditional cropping systems for their sustainability.

Implementing these policies can support the preservation of enough landraces for in situ evolution, which is crucial in the face of impending climate change. Furthermore, by making nutritious sources like millets available to the poor in the region, these policies may also help alleviate the prevalent malnutrition to some extent. It’s important to recognize that eradicating hunger is not the only objective in promoting healthy communities. Addressing malnutrition, which is a significant concern in this region, must receive equal emphasis.