India’s economic growth over the past few decades has been accompanied by concerning levels of chronic hunger, stunting, and wasting. Despite being a developing country, India ranks a lowly 94th out of 107 countries in the 2020 Global Hunger Index. Shockingly, around one-third of malnourished children in the world reside in India, with over 70% of them concentrated in eight states, including Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu. It is hard to comprehend such widespread malnutrition in a country with significant economic growth. Unfortunately, intergenerational malnutrition has been a significant public health and nutrition concern in India for several decades. The latest survey (NFHS-5) further validates this ongoing problem.

Now, new data suggest that child malnutrition might be worsening – fewer children in India are dying, but those who survive are more malnourished and anaemic in many states. Despite a fast-growing economy and the largest anti-malnutrition programme, India has the world’s worst level of child malnutrition. The government plans to pump in INR 1,23,580 crore over the next five years to tackle the problem. All the states with a high burden of malnutrition have the public distribution system in place to ensure that the poor, even in inaccessible areas, get food grains at subsidized rates. Yet, reports regularly appear both within and outside the country, highlighting child deaths due to malnutrition.

Table of Contents

According to the Registrar General of India, in 2010, under-five mortality in India was 59 per 1,000 live births, one of the highest in the world. In 2012, it was reported that 1.83 million Indian children die every year before they turn five and pinned malnutrition as the key reason for the deaths. The child may eventually die of a disease, but that disease was lethal because the child was unable to fight back due to malnutrition. All surveys indicate that India is slipping into a vicious cycle of malnutrition. Scientists say the initial 1,000 days of an individual’s lifespan, from the day of conception till he or she turns two, is crucial for physical and cognitive development. But more than half the women of childbearing age are anaemic and 33 per cent are undernourished, according to NFHS 2006. A malnourished mother is more likely to give birth to malnourished children.

According to the 2011 HUNGaMA (Hunger and Malnutrition) report, there has been a reduction in malnutrition rates in India. However, it still found that 42% of children under the age of five were underweight and 59% were stunted. A survey conducted across 112 rural districts by the non-profit Naandi Foundation highlights the impact of the world’s oldest anti-malnutrition program. Shockingly, 80% of mothers surveyed had not even heard of the term “malnutrition” in their local language. Despite these findings, it remains unclear whether the number of malnourished children has increased or decreased since the 2006 NFHS survey.

Arguments have emerged in favor of the WHO formula for measuring malnutrition. This reference was prepared by considering people from all backgrounds, including those living in poverty. The WHO standard maintains that children in poor countries will grow similarly to those in wealthier countries if given similar opportunities. However, the ongoing debate over the measurement of malnutrition fails to address some crucial determinants of childhood health.

Many people commonly associate poverty with malnutrition, and it is true that a significant portion of malnourished children come from impoverished families and states. However, rates of malnutrition are also prevalent in middle- and high-income households. As India continues to grapple with the pervasive issue of malnutrition, it is crucial to take a critical look at the less obvious factors that contribute to its high prevalence throughout the country.

Confusion over measurement

While the WHO formula is often used by countries, including India, to measure malnutrition since 2006, analysts argue that it is not a standard, but rather a reference. Malnutrition is a complex issue that is the result of 15 to 20 contributing factors, such as low literacy levels and poor access to clean drinking water and sanitation.

Interestingly, malnutrition rates in India are higher than in sub-Saharan African countries, despite India having a higher per capita income. Nearly 69% of Indians earn less than US $2 per day, while half of sub-Saharan Africa subsists on this amount. This discrepancy has led to a debate over the applicability of the WHO standard in India.

A research paper published in the Economic and Political Weekly in May of this year criticized the formula, pointing out that while India has made progress in other social indicators, it has lagged behind in reducing malnutrition. The paper attributed this to the formula’s flawed use of height and weight as yardsticks for measuring a child’s growth. This approach does not consider the genetic and nutritional disparities among populations, such as Indians not being genetically programmed to be as tall as the WHO standard expects.

The Indian government is set to use the WHO formula to estimate the number of malnourished children in the upcoming round of the NFHS survey, starting in 2014. However, medical and community health experts are divided on the formula’s accuracy, with some stating that the WHO growth chart, which is prepared using the formula, should not be used as a standard to measure malnutrition, as it only serves as a reference. The chart provides information on the ideal size of children from well-off backgrounds, such as those born to educated parents who have access to nutritious food, sanitation, and medical facilities, and it demonstrates how a child should grow in an ideal situation.

India is a vast country with individuals belonging to many ethnic groups. In certain communities, people are of short stature. This does not mean they are malnourished. The use of the WHO growth chart as a standard to decide malnutrition levels has led to confusion among ground-level health workers. At the village level, an Anganwadi worker is the first to identify a malnourished child. She registers every birth in her area and monitors the child’s growth at regular intervals. While the WHO formula uses three measures of physical growth-age, weight, and height to judge the nutritional status of a child, Anganwadi workers usually prepare the growth chart based on weight alone. If a child is detected underweight, which is a measure of malnourishment, the Anganwadi worker refers him or her to NRC for intensive nutrition treatment.

Facts of Anganwadi Centres

- Only 49% of under-six children who are registered for Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) benefits and go to Anganwadi centres have their weight monitored by anganwadi workers, leaving the rest of the children unmeasured.

- Anganwadi workers are not adequately trained to measure all indicators of malnutrition, including weight, height, and age, which results in inaccurate calculations.

- Most mini Anganwadis lack essential equipment like weighing and measuring machines, and 82% of Anganwadi centres suffer from scarcity of equipment and teaching aids.

- Anganwadi workers measure underweight while Nutrition Rehabilitation Centres (NRCs) measure wasting, leading to discrepancies in data. This also results in many children being refused admission, causing them to lose out on the crucial window of opportunity during their first 1,000 days of life.

- Those who receive treatment at NRCs need to visit every fortnight for two months of follow-up treatment, but parents, particularly those from tribal communities, are often unwilling to comply.

- Due to a lack of skills of Anganwadi workers, supervisors often do the final data entry, and if they find any inappropriate entries, they correct them without consulting the workers. This leads to significant data mismatch, which cannot be fixed as the data moves to the state government and then to the Centre.

Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres (NRCs)

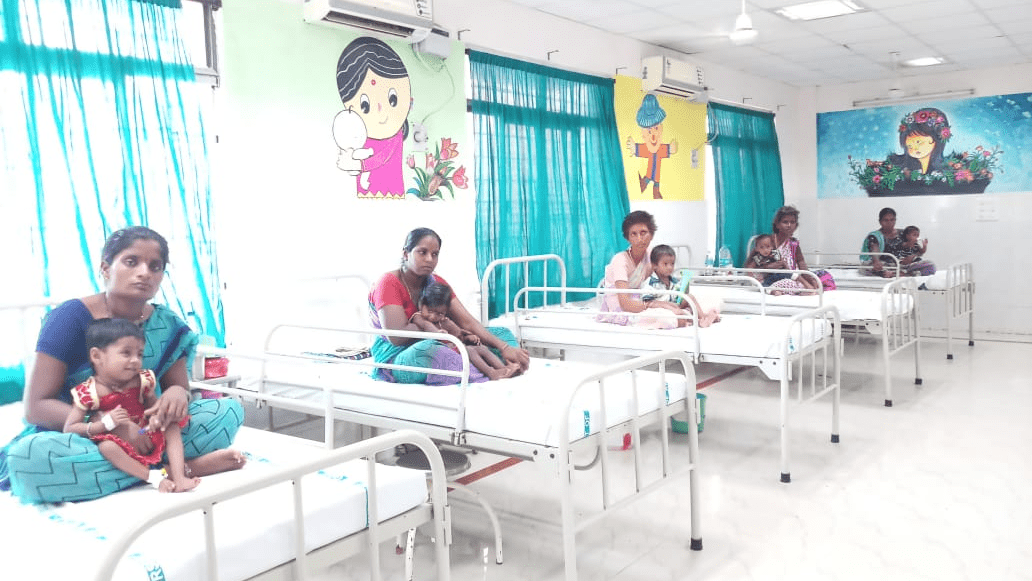

Nutritional Rehabilitation Centre (NRC) in Tirupati SVRR, Andhra Pradesh (Source)

Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres (NRCs) have different criteria for accepting a child as malnourished. Since they do not have the list of age for each child, they categorize children for wasting, which is measured based on height and weight. This is where discrepancies in measurement creep in, and many a time NRCs send back children referred by anganwadis for rehabilitation. The problem is that we see malnutrition as a disease. The health department cannot cure it. It is a community issue and people should be given proper food. NRCs fall under the health department.

The World Health Organization recommends measuring the mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) of a child to avoid discrepancies in determining malnutrition. Children with MUAC less than 115 mm are considered severely malnourished, those with 115-125 mm are moderately malnourished, and those with more than 125 mm are normal. However, this method is not widely used due to limited knowledge and skills of anganwadi workers.

Calculating and marking the mid-point of the arm after measuring its length is essential for measuring MUAC, a process that anganwadi workers find difficult. Instead, they prefer to track a child’s growth by weighing them. Consequently, India’s malnutrition data may not be accurate. ICDS records from March 2012 show that 62.8% of under-six children weighed at anganwadi centres were normal, while the rest were underweight or malnourished, representing a 10% decrease from NFHS 2006 estimates.

Improved WASH, a missing link?

Evidence shows malnutrition is high in areas where people defecate in the open. One missing piece of the malnutrition puzzle is social inequality. For example, girl children are more likely to be malnourished than boys, and low-caste children than upper-caste children.

But the most important aspect is sanitation. Most children in rural areas and urban slums are constantly exposed to germs from their neighbours’ faeces. This makes them vulnerable to the kinds of chronic intestinal diseases that prevent bodies from making good use of nutrients in food, and they become malnourished.

According to the Planning Commission’s evaluation report of the Total Sanitation Campaign, close to 72 per cent people in the country’s rural areas still defecate in the open. Every day, an estimated 100,000 tonnes of human excreta are left unguarded along river and stream banks, in open fields, on road sides and farms to contaminate water sources. According to Unicef, each gram of human excreta contains 10 million viruses, one million bacteria, 1,000 parasite cysts and 100 parasite eggs. Given the high population density in the country, this is sufficient to trigger widespread diseases. Children are more susceptible to such diseases.

Lack of sanitation and clean drinking water are the reasons high levels of malnutrition persists in India despite improvement in food availability. A few recent reports also provide evidence that lack of sanitation could be the key reason for high malnutrition.

A recent research paper published in science journal analyzed recently published data on the levels of malnutrition and open defecation in 112 rural districts. They found that 10 per cent increase in open defecation resulted in 0.7 per cent increase in both stunting and severe stunting. “The early-life disease environment is poor: over 70 percent of households defecate in the open and 71 out of every 1,000 babies born alive die before they turn one,” states the report. The researchers point out another missing piece of the malnutrition puzzle: two-thirds of all adults are literate in this region.

Today, India lags behind sub-Saharan Africa in terms of sanitation practices. About 56 per cent people defecate in the open across the country, including rural and urban areas. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 25 per cent the people defecated in the open in 2010, according to UNICEF and WHO, recent health surveys in the largest three sub-Saharan countries show that 31.1 per cent households in Nigeria, 38.3 households in Ethiopia and 12.1 per cent households in the Democratic Republic of Congo defecate in the open. This difference in sanitation practices between India and African countries explains the difference in malnutrition rate.

Even in India, good sanitation practices have helped curb malnutrition. The latest survey by the National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB), which conducts surveys in rural and tribal areas to find out nutritional status of people, also brings out this aspect. NNMB found that malnutrition level among children reduced over a period of time despite less intake of food. The improvement in nutritional status could be due to non-nutritional factors, such as improved accessibility to health care facilities, sanitation and protected water supply.

The latest Series on Maternal and Child Undernutrition Progress, includes three new papers that build upon findings from the previous 2008 and 2013 Series, which established an evidence-based global agenda for tackling undernutrition over the past decade. The papers conclude that despite modest progress in some areas, maternal and child undernutrition remains a major global health concern, particularly as recent gains may be offset by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Series reiterates that previously highlighted interventions continue to be effective at reducing stunting, micronutrient deficiencies, and child deaths and emphasizes the importance of delivering these nutrition interventions within the first 1,000 days of life. However, despite this evidence, programme delivery has lagged behind the science and further financing is needed to scale up proven interventions.

Malnutrition in India has multiple dimensions like inadequate access to food entitlements, calorific deficiency, protein hunger, and micronutrient deficiency. Undernutrition and stunting persist as roadblocks for the country. India is the home to almost one-third of all the world’s stunted children and half the world’s wasted children. Despite India’s 50% increase in GDP since 2013, more than one third of the world’s malnourished children live in India. Among these, half of the children under three years old are underweight. One of the major causes for malnutrition in India is economic inequality.

Malnutrition is Rising Across India – why?

Malnutrition in children has risen across India in recent years, sharply reversing hard-won gains, according to the latest government data. Experts say this is unsurprising. The reasons could be – India’s grinding Covid lockdown interrupted crucial government schemes that benefit hundreds of millions of women and children; and anganwadi workers, who were deployed in large numbers to monitor Covid and create awareness on how to prevent it, are yet to fully return to their original jobs. But that still doesn’t explain the rise in malnutrition rates in the years leading up to the outbreak of Covid-19 in 2020.

India’s latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS), which shows that children in several states are more undernourished now than they were five years ago, is based on data collected in 2019-20. The survey was conducted in only 22 states before the onset of the pandemic – so experts fear the results will be much worse in the remaining states, where the survey began after the lockdown ended.

Most Indian women (over 55%) are anaemic. Since undernourished mothers give birth to undernourished babies, experts say the worsening rate of malnutrition could be a result of women struggling to access nutrition benefits. They believe that migration is a reason to eke out a better living. But that also means being left out of massive government schemes that are mostly delivered at local level – so benefits aren’t easily transferred across districts or states.

Direct cash transfers, are supposed to solve this problem – but for migrants, that hasn’t happened either. This is despite the fact that there are three different schemes offering maternity and nutrition benefits to women. Here, experts say “exclusion” is one of the main reasons for rising malnutrition levels across India. While migration creates geographical exclusion, bureaucracy and its need for documentation creates a form of social and economic exclusion. Pregnant women after having two children have no maternity benefits. Also, in reality, despite the existence of government schemes, many women are unable to access them because of a lack of documents.

Sometimes, if the Aadhar card is not updated, or the name of the woman in the bank account is not changed from her father to her husband, then despite being in need of the nutrition, she is denied government benefits. Aadhar, the biometric government ID scheme, is a must-have for accessing nearly every social welfare programme in India. But a system that was meant to serve the poor more swiftly has often been accused of failing them. The poor have complained that linking the ID to their bank accounts or updating it with new information – such as when they migrate for work – involves multiple trips to government offices that they cannot afford. However, the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India has now declared such requirements as null and void.

Government Initiatives – Mission Poshan 2.0

The Ministry of Women and Child Development has issued Operational Guidelines regarding implementation of ‘Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0‘. The scheme has been approved by the Government of India for implementation during the 15th Finance Commission period 202l-22 to 2025-26.

Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 is an Integrated Nutrition Support Programme. It seeks to address the challenges of malnutrition in children, adolescent girls, pregnant women and lactating mothers through a strategic shift in nutrition content and delivery and by creation of a convergent eco-system to develop and promote practices that nurture health, wellness and immunity.

With a view to address various gaps and shortcomings in the on-going nutrition programme and to improve implementation as well as to accelerate improvement in nutrition and child development outcomes, the existing scheme components have been re-organized under Poshan 2.0 into the primary verticals given below:

- Nutrition Support for POSHAN through Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) for children of the age group of 06 months to 6 years, pregnant women and lactating mothers (PWLM); and for Adolescent Girls in the age group of 14 to 18 years in Aspirational Districts and North Eastern Region (NER);

- Early Childhood Care and Education [3-6 years] and early stimulation for (0-3 years);

- Anganwadi Infrastructure including modern, upgraded Saksham Anganwadi; and Poshan Abhiyaan

The Objectives of Poshan 2.0

- To contribute to human capital development of the country;

- Address challenges of malnutrition;

- Promote nutrition awareness and good eating habits for sustainable health and wellbeing;

- Address nutrition related deficiencies through key strategies.

Poshan 2.0 focusses on Maternal Nutrition, Infant and Young Child Feeding Norms, Treatment Protocols for SAM/MAM and Wellness through AYUSH practices to reduce wasting and under-weight prevalence besides stunting and anemia, supported by the ‘Poshan Tracker’, a new, robust ICT centralised data system which is being linked with the RCH Portal (Anmol) of MoHFW.

Examples

Best Practices which have won the PM’s Award for Excellence for promotion of Jan Bhagidari in Poshan Abhiyaan on 21st April 2022 are as follows:

1. Mission Sampurna Poshan in Asifabad, Telangana

Under the program, in the First Phase, 33 Food Festivals, 10 Millet recipe trainings were conducted covering 225 Anganwadi, Millet recipes, cooking videos were made in local language and circulated through WhatsApp, and YouTube. Anganwadi workers made door-to-door visits daily to monitor healthy food intake. To promote millets, subsidized seeds were distributed to 2500 households on a pilot basis. 80% of beneficiaries are now consuming millets.

2. Mera Bachccha Abhiyaan Model in Datia, Madhya Pradesh

Mera Bacchcha Abhiyan model saved many children. Identification of malnourished children, weight of children 0-5 years were taken by AWW at all 990 AWCs by conducting intensive weighing campaign. The process was repeated every 3 months. The highlight of the Abhiyan was the Adopter who took the responsibility of nurturing the SAM child through regular interventions with the family of the child. Datia district has also compiled a list of such Adopters who have been recruited for the purpose.

3. Project Sampoorna in Bongaigaon, Assam

During Poshan Maah in September 2020, over 2400 children were identified as malnourished. To address this challenge, the concept of ‘Buddy Mothers’ was introduced wherein two mothers form a pair, one with a healthy child, the other with a malnourished child. They exchanged best practices and worked on diet charts to monitor the daily food intake of their children. The local Government arranged for milk and egg on alternate days for all identified children for the first 3 months.

Other examples of best practices include “Suposhan Panchayat” and Model Organic Terrace Gardens in AWCs in Bihar; Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition in Madhya Pradesh; Nutri-Gardens at AWCs and in backyards of households in Gujarat; Mobile Nutri-Gardens in Urban areas and distribution of mahua laddoos to PWLM in tribal areas in Telangana, mobile NRCs and Poshan Mulyankan Cards for MAM/SAM children in Chandigarh, etc.