Sandalwood, scientifically known as Santalum album and commonly referred to as “Chandan” in India, holds a significant position as one of the most prized timber resources worldwide. Its heartwood, found within the inner core of the tree’s stem, and its oil are highly sought-after commodities in the global market. The Sandalwood tree has been classified as a threatened, endangered, and vulnerable species according to the IUCN Red List.

Table of Contents

A Valuable Agroforestry Species

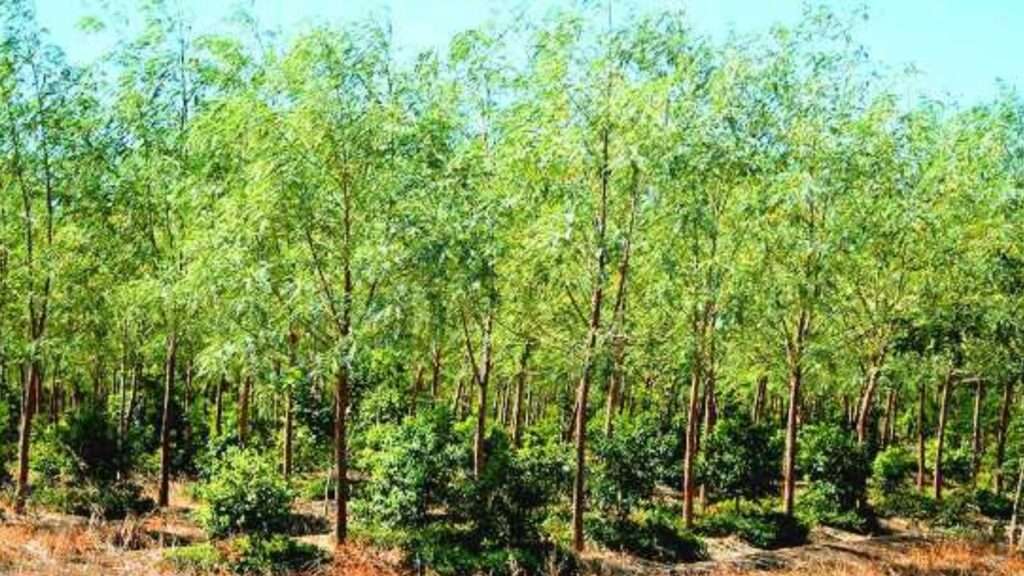

Sandalwood trees naturally thrive in the Nandapur Block of the Koraput district in Odisha. What sets these trees apart is their hemi-parasitic nature, which means they can live as parasites under natural conditions while retaining their ability to photosynthesize to some extent. This unique characteristic, along with their adaptability to semiarid regions and their potential to coexist with horticultural species as secondary hosts, makes sandalwood a highly valuable agroforestry species.

Expansion of Sandalwood Farming in Non-Traditional Regions

The relaxation of regulations concerning sandalwood cultivation in 2001 and 2002 has sparked significant interest among farmers and stakeholders throughout India. The lucrative prices and high demand for sandalwood heartwood have motivated farmers and stakeholders to venture into sandalwood farming, particularly in non-traditional regions across various states such as Gujarat, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra over the past decade. This trend reflects a growing enthusiasm for sandalwood cultivation beyond its traditional areas.

Also read – Red Sanders – An Endangered Species

Challenges and Prospects for Sandalwood Farming

The potential of sandalwood trees in both natural and naturalized forested areas, as well as existing farming systems and other silvi-horticultural systems throughout India, is vast. This article explores the current challenges and future prospects for expanding livelihood opportunities and boosting farm income levels. Additionally, it provides suggestions for promoting sandalwood farming practices across the country, taking into consideration the immense possibilities it holds for sustainable economic growth.

Smuggling and Shifting Cultivation as Threats

Despite once boasting sandalwood plantations spanning over 10,000 hectares of land, Koraput district now suffers from a significant decline, with only 2,000 sandalwood trees remaining. The valuable trees have become victims of smuggling activities and Podu chas (shifting cultivation) practiced by local tribals.

The establishment of sandalwood plantations in the region can be traced back to the patronage of the kings from the erstwhile Jeypore dynasty in the 19th century. These kings imported numerous sandalwood saplings from Mysore and distributed them to tribal heads known as “Nayaks” in Nandapur, Koraput, Jeypore, and Lamtaput for widespread plantation across the district. The motive behind these plantations, conducted in the early 1950s in the forest ranges of Jeypore, Nandapur, and Koraput, was to fulfill the sandalwood requirements of temples within the Jeypore kingdom.

On special occasions like Rath Yatra and Dussehra, pieces of sandalwood were offered as gifts to the Jagannath temple in Puri and other popular Devi shrines in the state. At that time, sandalwood smuggling was virtually nonexistent, as the trees held sacred significance among the tribals. However, after the abolition of the Zamindari system in 1956, the felling and smuggling of sandalwood trees began.

Forest Department Initiates Reforestation Efforts

During the 1990s, the illegal smuggling of sandalwood to states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh reached alarming levels. As a consequence, the number of sandalwood trees witnessed a steady decline, as the Forest Department struggled to curb the illicit felling and smuggling activities.

Traditionally, around 50 quintals of sandalwood were donated annually from the district to various temples across the state for rituals. However, for the past two years, this donation has ceased due to an insufficient number of trees. Additionally, during the Nabakalebara in 2015, the Puri temple received only a minimal quantity of sandalwood from the district’s forest wing.

In a delayed response to the situation, the Forest Department has now taken the initiative to cultivate sandalwood trees across 2,000 hectares of land in the Jeypore and Koraput forest divisions over the next two years. The aim is to replenish the declining population of sandalwood trees and address the shortage that has affected the temple donations. The rampant smuggling of sandalwood from Koraput to states like Bihar, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh in the 1990s has prompted this belated action to restore the region’s sandalwood resources.

Expanding Sandalwood Cultivation in Agroforestry Practices

Santalum album, commonly known as sandalwood, exhibits remarkable versatility in terms of its ability to thrive in various soil types, including gravelly loam and sandy clay soils. The prevalent soil type where sandalwood occurs is red ferruginous loam with underlying gneiss, which is typically low in nutrients. It can tolerate soil pH levels up to 9.0 but cannot thrive in waterlogged areas.

The species can flourish in regions with rainfall ranging from 500 mm to as high as 5000 mm, enduring long dry seasons and elevations from sea level up to 1800 meters. Furthermore, sandalwood trees can even grow outside this climatic range and withstand extreme temperatures ranging from 4 to 46 degrees Celsius. This adaptability gives sandalwood a distinct advantage, enabling it to thrive under challenging environmental conditions. As a hemi-parasite, sandalwood requires a primary host, intermediate host, and long-term secondary host, making it highly suitable for agroforestry practices.

The demand for sandalwood has surged, thanks to the Karnataka Forest (Amendment) Act 2001, which grants legal entitlement to the sandalwood tree on private lands. This has led to increased interest from private entrepreneurs and farmers in establishing private plantations. The high demand and lucrative prices of sandalwood heartwood have motivated individuals to cultivate sandalwood on their farmlands, despite the need for better protection measures.

Also read – Importance of Environment to Human Life

In sandalwood-based agroforestry, a spacing of 6×3 meters with Amla (Emblica officinalis) planted in between sandalwood in a quincunx design has shown promising results. Additionally, incorporating the cultivation of annual crops like horse gram and other pulses further enhances the potential of the system. While the cost of establishing sandalwood-based agroforestry plantations may be slightly higher due to additional intercultural operations, the periodic returns from horticultural crops can compensate for this investment. Sandalwood plants in agroforestry settings have demonstrated robust growth parameters, likely due to improved soil physicochemical properties.

However, there is a lack of data on sandalwood growth and heartwood formation specifically in agroforestry situations. To accommodate higher plant densities, a spacing of 4×4 meters with a long-term host like Jhaun (Casuarina equisetifolia) in the center, also in a quincunx design, shows promise.

The total cultivation cost over a 15-year period amounts to INR 19.87 lakhs per hectare, while the total benefits reach around INR 143 lakhs per hectare. Protection costs constitute nearly 30% of the total cost. The revenue generated from sandalwood tree extraction and processing over 15 years amounts to INR 25,000 per tree (including sapwood, heartwood, and mixed wood).

These findings highlight the potential for expanding sandalwood cultivation within agroforestry practices, considering its adaptability, economic prospects, and the need for further research to optimize growth and heartwood formation in such systems.

Addressing Challenges in Sandalwood Farming

One of the major challenges faced in sandalwood farming in India is ensuring the physical protection of mature trees, particularly from the 10th year onwards when they become susceptible to theft. To safeguard the plantations, farmers must invest in tamper-proof boundary walls and employ security staff, including trained dogs, especially in larger-scale plantation areas.

Some companies are also exploring the use of remote surveillance systems similar to home security systems, although these are still in the research and development phase and have not been fully commercialized yet. Another significant challenge arises from the long gestation period of sandalwood, which typically ranges from 15 to 20 years under farming conditions. During this period, sustaining a steady income becomes crucial to cover the costs of protection and maintenance.

In the realm of sandalwood agroforestry, an opportunity lies in incorporating horticultural species as secondary hosts along with short-term primary hosts and annual intercrops whenever possible. Farmers across India have experimented with horticulture crops such as Pomegranate, Guava, Citrus, Jamun (Syzigium cumini), grafted mango, Amla, and Sitaphal/Custard apple (Annona squamosa) with varying degrees of success.

However, there is a lack of standardized package of practices available for horticulture crops, taking into account factors such as soil type, climate, and market conditions. Developing region-specific guidelines and sharing best practices would greatly benefit farmers in maximizing the potential of sandalwood agroforestry and enhancing overall productivity.

Efforts to address these challenges and provide support to sandalwood farmers should focus on strategies for protecting mature trees, exploring innovative surveillance systems, devising income-generation models during the long gestation period, and promoting research and knowledge exchange regarding the integration of horticultural crops in sandalwood agroforestry. By addressing these challenges and harnessing the opportunities available, the sustainable cultivation of sandalwood can be fostered, leading to enhanced economic benefits for farmers and the preservation of this valuable resource.

Also read – Effects of Deforestation on Humans

The Versatility of Sandalwood Essential Oil: Benefits and Applications

Sandalwood Essential Oil is renowned for its wide range of benefits and applications, making it a highly versatile essential oil. Its historical significance as a spiritual incense dates back to ancient times, and it continues to be valued for its spiritual properties. When used for chakra work, Sandalwood Essential Oil exhibits profound grounding qualities. On an emotional level, it promotes a sense of calmness and inner peace, making it beneficial for managing stress, depression, and boosting self-esteem. Additionally, Sandalwood Essential Oil is often recognized as an aphrodisiac.

Sandalwood holds a rich historical significance as an incense for spiritual purposes, dating back to ancient times. Its essential oil possesses profound grounding properties and proves beneficial for chakra alignment. On an emotional level, Sandalwood Essential Oil has a calming effect, promoting inner tranquility and aiding in cases of stress, depression, or low self-esteem. Apart from its aromatic presence in perfumes and air fresheners, sandalwood oil derives from the valuable Santalum album, also known as the East Indian Sandalwood tree. Remarkably, beyond its delightful fragrance, sandalwood oil may also offer various health benefits due to its unique properties.

The aromatic profile of Sandalwood Essential Oil is characterized by its rich, woody, and sweet scent. Its delightful fragrance makes it a popular choice for perfumery and fragrancing, appealing to both men and women. As a base note, it contributes to creating well-rounded blends. Beyond its aromatic presence, Sandalwood Essential Oil offers various therapeutic benefits. It is commonly used to address conditions such as bronchitis, chapped skin, depression, dry skin, laryngitis, leucorrhea, oily skin, scars, sensitive skin, stress, and stretch marks.

With its diverse range of applications in spirituality, emotional well-being, perfumery, and skincare, Sandalwood Essential Oil remains a highly valued and cherished oil for its numerous benefits and versatility.

Suggestions to Promote Sandalwood-Based Agroforestry in India

To overcome the significant challenges faced in sandalwood farming and meet the expectations of the farming community, a concerted effort is required to address technical and management problems. By implementing certain precautions during the procurement of planting stock and maintaining sandalwood plantations, both the quality and quantity of the output can be improved.

Here are some suggested steps to promote sandalwood cultivation:

- Procure Quality Planting Material (QPM) from certified nurseries: Farmers should obtain sandalwood plants from accredited nurseries that provide quality planting material. Certification agencies such as ICFRE, State Forest Departments, or public sector undertakings like KSDL in Karnataka can play a role in ensuring reliable sources.

- Follow scientific management practices: Adhere to scientific guidelines for sandalwood farming, including proper spacing, host management, intercropping, pruning, fertilization, drip irrigation, and pest management. Beware of self-proclaimed experts and consult reliable sources, preferably entering into MoUs with government agencies for ongoing support.

- Explore remote surveillance and protection systems: Instead of relying solely on physical protection measures, consider installing remote surveillance and protection systems offered by private companies. These technologies can help enhance the security of growing sandalwood trees.

- Review rules and regulations for procurement: Explore options to enhance profits for cultivators by examining the rules and regulations related to procurement from farmers by private entities. Market liberalization can be beneficial, and policy and governance need to be considered in this regard.

- Encourage financial support and insurance schemes: Urge nationalized banks to introduce finance schemes specifically for sandalwood cultivation. Insurance companies should also develop tree insurance schemes similar to those available for horticultural crops. Additionally, subsidies and incentive schemes provided by State Medicinal Plant Boards can further encourage sandalwood cultivation.

- Promote Joint Forest Management (JFM): Encourage village forest protection committees with information, support, and planting materials to cultivate and sustainably manage sandalwood trees in their forests. Clearly define benefit-sharing mechanisms in line with the Forest Rights Act, 2006, to ensure the involvement of local communities.

- Establish sandalwood-based agroforestry demonstration plots: Government initiatives should include setting up demonstration plots that combine sandalwood with horticultural species as secondary hosts. These plots can showcase the latest scientific technologies and research and development inputs to educate and inspire farmers.

By implementing these initiatives, sandalwood cultivation combined with horticulture can be promoted effectively throughout the country, leading to sustainable growth in this sector.