The warmest decade since record keeping began 140 years ago was 2010 to 2019, according to a NOAA and NASA analysis that was released today. The analysis also showed that ocean temperatures were the highest they had ever been and that 2019 was the second-hottest year ever measured. The authors of the report attribute the continuation of global warming to emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

As the globe finally faced the effects of climate change, these warmer temperatures contributed to a number of catastrophic disasters. The study is the most recent to support the idea that things might get worse if nothing is done to reduce emissions. A lot of people realized this decade that climate change is real, that it is already occurring, and that it might very quickly grow much, much worse.

A slew of tragic, dramatic, and fatal occurrences occurred over these ten years, punctuating them. Communities were fundamentally altered by hurricanes like Sandy, Maria, and Harvey, leaving wounds that haven’t fully healed. Communities all around the country and the world were forced into deadly heat waves by increasingly powerful heat waves. Thousands of acres were destroyed by wildfires in a matter of seconds.

There is no disputing the driving force behind the developments. Extra heat is being trapped close to the surface of the Earth as a result of steadily rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, mostly brought on by people burning fossil fuels. This causes the entire Earth to warm. As changes ripple through the oceans, atmosphere, soil, rocks, trees, and every other living thing on the earth, the result is both obvious—a hotter planet—and tremendously complex.

Leah Stokes, a specialist in climate policy at the University of California, Santa Barbara, says, “God, this was a dreadful decade.” “Let’s lessen the badness of the next one.”

The Past Decade Damaged All Kinds Of Records

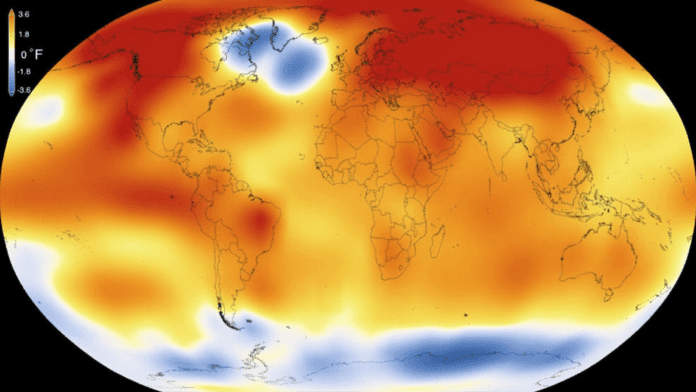

Anyone who was paying attention might see a warning sign flashing because the most recent decade was the hottest ever recorded. The last five years alone were the hottest span ever recorded, with yearly temperatures across the years hovering just less than 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) higher presently than they did from 1950 to 1980. Approximately 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit (0.94 degree Celsius) hotter than that long-term average, 2019 is on track to be the second-hottest year ever.

Although that amount might not seem like much, its effects are considerable. The risk of extremely hot incidents increases with each small change in the average. And even minor changes in the total quantity of heat held in the atmosphere, oceans, and water can have a significant impact on the globe.

For instance, according to scientific estimates, the world was only on average 10.8 degrees F (6 degrees C) colder during the previous ice age, which occurred roughly 20,000 years ago. However, North America was then covered by a massive ice sheet that reached as far south as Long Island. The average temperature hardly slightly changed, but the planet had a very different appearance.

The hottest temperatures are also gradually rising, as predicted by scientists. The likelihood of the exceptionally hot moments increases as the average moves upward. The frequency of “extreme” heat occurrences has increased over the previous ten years, and this trend is only projected to continue.

Another significant aspect of the global warming is that it is not occurring consistently throughout time or space. Summers are warming more quickly than winters. The difference in minimum temperatures from 2009 to 2018 (the most recent ten years for which we have records; 2019 records are not yet available) was 1.34 degrees Fahrenheit.

A wide range of uncomfortable, ecosystem-reshaping impacts accompany milder winters: A mismatch between pollinator and plant flowering periods results from earlier springs. Throughout the summer and fall, there is less water available due to less snowfall, more rain, and earlier snowmelt. Where there should be ice, there are instead unfrozen lakes, thawing permafrost, and open water.

The oceans have undergone an even more dramatic and significant transformation. The ocean smooths out the signal by incorporating all the warming that has occurred over previous years, whereas air temperatures have a tendency to fluctuate from year to year in response to large patterns like El Nino, the recurring weather event that warms the Pacific Ocean. It communicates with us clearly by responding to changes occurring above its surface more gradually and steadily.

The ocean has absorbed over 90% of all the extra heat contained by human-caused climate change, and its surface temperatures are already showing this. Bigger changes—changes that could impact weather patterns over the entire planet—may be arriving sooner than we think, including marine heat waves similar to those we experience on land.

How Did People’s Views On Climate Change Evolve?

Climate change’s physical patterns are becoming more and more obvious. Those bodily changes are being accompanied by a change in mindsets. Americans were interested in the topic of climate change during the 2000s, according to Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Discussions over how to approach the problem were sparked by an IPCC report from 2007 as well as by political communities. Speaking out were scientists.

But between 2008 and 2010, for a variety of political and societal reasons, even the notion that the climate was changing—let alone whether remedies should be pursued—dropped rapidly in the United States. Leiserowitz claims that the first half of the decade was devoted reviving interest in and attention to climate change as a significant issue.

At the same time, researchers have created new methods to quantify how much more likely a certain occurrence—such as a hurricane, heat wave, or wildfire—was as a result of climate change. They are able to immediately connect a meteorological occurrence to the larger patterns of change. According to him, this explicit linking is altering how individuals view the larger problem.

Public interest in and worry about climate change have grown significantly during the last few years. By this year, 67 percent of the U.S. adults the Yale program questioned believed that global warming was occurring, up from 59 percent in 2010. In 2009, 31% of respondents believed that global warming would negatively affect them personally; by this year, that percentage had increased to 42%.

Many people are beginning to make connections, according to Leiserowitz. “Oh my god, is this a result of climate change? Additionally, a bigger portion of the populace is beginning to notice it and wonders, “Huh, what’s up with all these record-breaking events after record-breaking events? Are these issues related?

Stokes claims, “It was a pretty horrible decade.” “I’d say we missed nine years of the decade, but the past 12 months have seen real progress. There’s a whole new vitality and energy,” and she claims that this may be a hint that the upcoming decade of climate change will hopefully be different from the previous one.

Also read: