Organic farming in India grows only where chemical use was always low — and current policies do not help farmers in high-input regions make the shift.

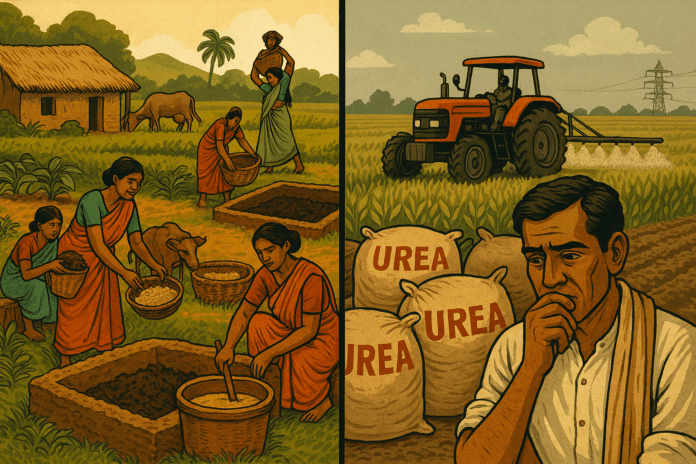

Why is organic or natural farming restricted only to tribal dominated and difficult to reach villages? We come across examples of organic or eco-villages where the farmers grow crops with natural inputs such as manure, compost and agri-inputs only in the hinterlands of Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Jharkhand or Odisha and the North Eastern region. Even though there have been several efforts by Government and NGOs, the number of such “truly organic villages” and farmers is limited. Efforts to promote chemical-free farming in non-tribal and “advanced” regions have not borne the desired result. The prime concern farmers have raised is (a) loss of production, and (b) lack of organic farm inputs.

During a recent field visit in Odisha’s coastal belt, a paddy farmer in Jagatsinghpur summed up the sentiment succinctly: “We cannot afford a bad season just to test a new method. Urea works; organic inputs don’t reach us on time.” This view reflects a nationwide pattern. Farmers in intensive agriculture zones—Punjab, Haryana, parts of Bihar and Andhra Pradesh—are reluctant to reduce chemical use due to fears of yield loss and uncertain market premiums.

Despite policy pushes, organic and natural farming in India remain largely confined to tribal, hilly, and hard-to-reach areas. This is not accidental—it is shaped by economic incentives, farming systems, market signals, and input ecosystems.

Table of Contents

Why Organic Farming Hasn’t Scaled Beyond the Hinterland

A first root cause lies in the structural bias of Indian agriculture toward high-input, high-yield systems — particularly in “advanced,” high-productivity regions. As per a 2022-analysis, average fertiliser consumption in India has grown from about 12.4 kg/ha in 1969 to around 190 kg/ha today, with states like Punjab, Haryana, Bihar and Telangana routinely exceeding 200 kg/ha. Such intensive reliance on chemical fertilisers and pesticides has shaped a farming model that is optimized for chemical inputs; switching to organic or natural inputs in this context can lead to substantial yield drops, at least in the initial years, which farmers, especially those cultivating cash or staple crops at scale, are often unwilling to risk.

Moreover, access to organic inputs remains one of the biggest bottlenecks. In a conversation earlier this year, a senior Odisha Agriculture Department official noted: “Our biggest challenge is not farmer willingness; it’s the absence of reliable, affordable bio-input supply chains.” While Odisha’s Organic Farming Policy (2018) and SAMRUDDHI Agriculture Policy (2020) encouraged cluster-based organic production, many farmers report that compost, biofertilisers, and natural pesticides are either too costly or simply unavailable at scale.

Studies mirror these field experiences. Although India hosts more than 2.3 million organic producers, certified organic farmland is still only about 4.5 million hectares—around 2.5% of the country’s cultivated area. Even among farmers trained under government schemes, many end up using compost alongside urea rather than replacing chemical fertilisers entirely. Yield risks, labour demands, certification hurdles, and uncertain price premiums discourage full conversion.

As one FPO leader from Rayagada mentioned: “Organic is viable here because our farmers never depended much on chemicals. But convincing coastal farmers is a different battle.”

Government Efforts: Progress, but Uneven and Slow

The Government of India has launched an array of initiatives—Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY), the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA), and recently the National Mission on Natural Farming (NMNF). Certification systems under NPOP and APEDA have improved export potential, while platforms like Jaivik Kheti have connected producers to buyers.

Odisha, too, has been proactive. With its Odisha Organic Farming Policy, 2018 and flagship “Kalinga Organic” branding efforts, the state has identified over 2 lakh hectares for organic promotion. Many of these are in Kandhamal, Koraput, Mayurbhanj and Keonjhar—districts with strong tribal presence and low chemical dependency.

Yet, despite this expanded policy canvas, structural constraints persist. Bio-input production is fragmented. Certification remains costly. Many clusters struggle after initial funding ends. A representative from a leading NGO in Kalahandi put it bluntly: “Government schemes create clusters, but not ecosystems. Organic farming thrives only where communities already know how to live with low inputs.”

There is significant lack of awareness, technical knowledge, and supply infrastructure for organic farming, especially in non-forest and non-tribal zones. Many farmers reportedly lack understanding of organic methods — composting, bio-fertilizer management, integrated pest management — and even if interested, find organic inputs scarce, expensive or logistically difficult to procure. The certification and marketing infrastructure for organic produce remains patchy; high certification cost and lack of reliable supply chains deter both farmers and consumers.

The transition cost — in terms of yield risk, time, labour, certification and uncertain premiums is high, making organic farming unattractive to large, market-oriented farmers. A pan-India empirical survey showed that under organic farming compared to conventional in crops like paddy, soybean and wheat, yields were reduced by 8–9%, while production costs did come down (by ~14–17%). However, gross revenue under organic was lower by ~8–9%. Profitability gains were marginal: e.g. only ~5–6% for paddy, ~3.2% for soybean and ~0.2% for wheat. In such a scenario, unless there is assured market premium or subsidy support, the “business case” for shifting to organic remains weak for many farmers.

If We Continue Like This: The 2050 Outlook

If India continues on its present trajectory — with incremental cluster-based programmes, limited incentives, and uneven supply-chain development — the overall share of truly organic or natural farming is unlikely to exceed 5–7% of total cultivated land by 2050. Certified or in-conversion acreage may expand numerically, but most growth will remain concentrated in tribal, rainfed and remote geographies where baseline chemical use is already low. High-input, irrigated regions — which account for the bulk of India’s food production — will largely continue business-as-usual practices due to yield risks and market constraints. Consequently, the national food system will remain structurally dependent on synthetic fertilisers, implying persistent soil nutrient imbalance and plateauing soil organic carbon levels.

For Odisha, the scenario is similar. Tribal belts will contribute most of the certified acreage, while coastal and irrigated districts—the state’s agricultural powerhouse—will remain anchored to chemical-intensive practices. Soil organic carbon levels, already declining in many districts, may stabilise only marginally. Nutrient imbalances, particularly nitrogen overuse, will persist.

In short, India risks building an organic ecosystem that is symbolically large but substantively small.

What Needs to Change: A Shift from Clusters to Systems

To break out of this low-impact trajectory, India needs a system-wide realignment—moving beyond clusters and demonstration plots to reshape incentives, markets and input ecosystems.

1. Transition Incentives Must Cover Risks

Farmers need robust, time-bound support to endure yield fluctuations during the conversion phase. This includes direct compensation, assured procurement for select organic crops, and crop diversification incentives. Without risk sharing, larger and market-oriented farmers will continue to stay away.

2. Build Local Bio-input Hubs at Scale

Input scarcity is perhaps the most urgent problem. SHGs, women’s collectives, and FPOs can run community-level biofertiliser and compost units if supported through capital grants and technical training. Odisha, with its strong Mission Shakti network, is uniquely positioned to lead such a model.

3. Create Commodity-Specific Organic Value Chains

Organic farming will not scale unless farmers see reliable premiums. States must pick 5–6 crops—such as turmeric, millets, pulses, or vegetables—and build full value chains around them, including storage, processing, branding and market partnerships.

4. Reform Subsidies to Promote Soil Health

India’s fertiliser subsidy—dominated by urea—distorts soil nutrient balance. Gradually redirecting a portion of this subsidy toward soil carbon restoration, organic inputs, and integrated nutrient management can improve both sustainability and farmer incomes.

5. Strengthen Extension and Farmer-Led Learning

Organic transitions succeed where knowledge flows. District-level agroecology training, farmer field schools, and digital advisory services can help farmers adopt regenerative practices with confidence.

A Moment of Choice

Organic farming is not merely an environmental ideal; it is central to restoring India’s soil health and ensuring long-term food security. Odisha and India have made notable progress, but the gaps remain deep and systemic. As farmers across districts repeatedly told me: “We are willing, but the system is not ready.”

If policymakers can address these structural challenges with urgency and coherence, the next two decades could see organic and natural farming evolve from isolated success stories to a mainstream agricultural pathway. If not, India may continue celebrating organic “pockets” while missing the opportunity for a more resilient, sustainable and farmer-led future.

Also read – The Four Fundamental Principles of Environmental Law

Author: Sibabrata Choudhury - A social entrepreneur and public policy professional working at the intersection of rural livelihoods, land rights, and technology-driven development, with experience across agriculture, land reform, climate resilience, and grassroots governance.